Starfish embryos swim in formation like a “living crystal”

Their swirling, clustering behavior might someday inform the design of self-assembling robotic swarms.

In its earliest stages, long before it sprouts its signature appendages, a starfish embryo resembles a tiny bead, spinning through the water like a miniature ball bearing.

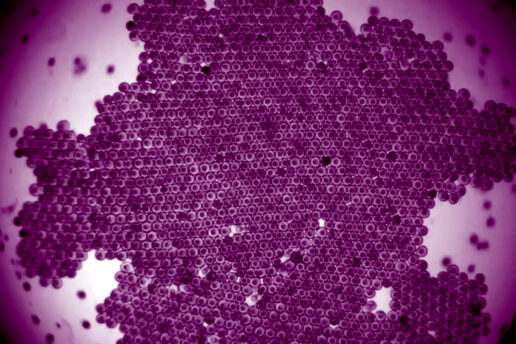

Now, MIT scientists have observed that when multiple starfish embryos spin up to the water’s surface, they gravitate to each other and spontaneously assemble into a surprisingly organized, crystal-like structure.

Even more curious still, this collective “living crystal” can exhibit odd elasticity, an exotic property whereby the spinning of individual units — in this case, embryos — sets off much larger ripples across the entire structure.

The researchers found this rippling crystal configuration can persist over relatively long periods of time before dissolving away as individual embryos mature.

“It’s absolutely remarkable — these embryos look like beautiful glass beads, and they come to the surface to form this perfect crystal structure,” says Nikta Fakhri, the Thomas D. and Virginia W. Cabot Career Development Associate Professor of Physics at MIT. “Like a flock of birds that can avoid predators, or fly more smoothly because they can organize in these large structures, perhaps this crystal structure could have some advantages we’re not aware of yet.”

Beyond starfish, she says, this self-assembling, rippling crystal assemblage could be applied as a design principle, for instance in building robots that move and function collectively.

“Imagine building a swarm of soft, spinning robots that can interact with each other like these embryos,” Fakhri says. “They could be designed to self-organize to ripple and crawl through the sea to do useful work. These interactions open up a new range of interesting physics to explore.”

Fakhri and her colleagues have published their results in a study appearing today in Nature. Co-authors include Tzer Han Tan, Alexander Mietke, Junang Li, Yuchao Chen, Hugh Higinbotham, Peter Foster, Shreyas Gokhale, and Jörn Dunkel.

Spinning together

Fakhri says the team’s observations of starfish crystals was a “serendipitous discovery.” Her group has been studying how starfish embryos develop, and specifically how embryonic cells divide in the very earliest stages.

“Starfish are one of the oldest model systems for studying developmental biology because they have large cells and are optically transparent,” Fakhri says.

The researchers were observing how embryos swim as they mature. Once fertilized, the embryos grow and divide, forming a shell that then sprouts tiny hairs, or cilia, that propel an embryo through the water. At a certain point, the cilia coordinate to spin an embryo in a particular rotational direction, or “chirality.” Tzer Han Tan, one of the group members, noticed that as embryos swam to the surface, they continued spinning, toward each other.

“Once in a while, a small group would come together and sort of dance around,” Fakhri says. “And it turns out there are other marine organisms that do the same thing, like some algae. So, we thought, this is intriguing. What happens if you put a lot of them together?”

In their new study, she and her colleagues fertilized thousands of starfish embryos, then watched as they swam to the surface of shallow dishes.

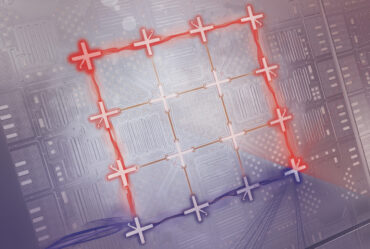

“There are thousands of embryos in a dish, and they start forming this crystal structure that can grow very large,” Fakhri says. “We call it a crystal because each embryo is surrounded by six neighboring embryos in a hexagon that is repeated across the entire structure, very similar to the crystal structure in graphene.”

Jiggling crystals

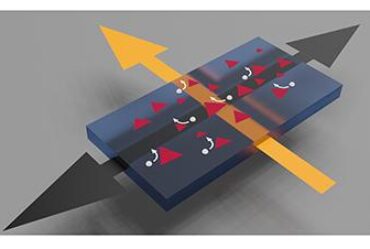

To understand what might be triggering embryos to assemble like crystals, the team first studied a single embryo’s flow field, or the way in which water flows around the embryo. To do this, they placed a single starfish embryo in water, then added much smaller beads to the mix, and took images of the beads as they flowed around the embryo at the water’s surface.

Based on the direction and flow of the beads, the researchers were able to map the flow field around the embryo. They found that the cilia on the embryo’s surface beat in such a way that they spun the embryo in a particular direction and created whirlpools on either side of the embryo that then drew in the smaller beads.

Mietke, a postdoc in Dunkel’s applied mathematics group at MIT, worked this flow field from a single embryo into a simulation of many embryos, and ran the simulation forward to see how they would behave. The model produced the same crystal structures that the team observed in its experiments, confirming that the embryos’ crystallizing behavior was most likely a result of their hydrodynamic interactions and chirality.

In their experiments, the team also observed that once a crystal structure had formed, it persisted for days, and during this time spontaneous ripples began to propagate across the crystal.

“We could see this crystal rotating and jiggling over a very long time, which was absolutely unexpected,” she says. “You would expect these ripples to die out quickly, because water is viscous and would dampen these oscillations. This told us the system has some sort of odd elastic behavior.”

The spontaneous, long-lasting ripples may be the result of interactions between the individual embryos, which spin against each other like interlocking gears. With thousands of gears spinning in crystal formation, the many individual spins could set off a larger, collective motion across the entire structure.

The researchers are now investigating whether other organisms such as sea urchins exhibit similar crystalline behavior. They are also exploring how this self-assembling structure could be replicated in robotic systems.

“You can play with this design principle of interactions and build something like a robotic swarm that can actually do work on the environment,” she says.

This research was supported, in part, by the Sloan Foundation and the National Science Foundation.